Hopkins Insider met with Hopkins alumna Janice Bonsu, ’15 to learn about her Hopkins experience and how it has impacted her post-grad life.

This transcript has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Can you tell us a little about yourself?

My name is Janice Bonsu. I graduated in 2015, majored in neuroscience and was on the pre-med track. I’m now an orthopedic surgery resident at the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

In my first year at Hopkins, I did ROTC, and while I didn’t end up graduating with them, I still ended up joining the military. During college, I realized I wanted to aim towards the medical corps and undergraduate ROTC is geared more toward officer leadership.

From the time you started Hopkins to the time you graduated, how did your academic and/or career interests evolve?

I always wanted to do something in healthcare. I never knew what “public health” was until I went to Hopkins. I quickly realized that I wanted to engage in healthcare through public health. But I still studied neuroscience because I found it interesting, and the mentors in the department were amazing.

I worked with one of the 21st Century City Initiatives professors, Dr. Edin, on a community health project in the summer of 2015 after the Baltimore Uprising. I was so engaged that it inspired me to pursue a Master of Public Health, which I did at the University of Pennsylvania. During that time, I did more community work. Eventually, my public health studies led me to Ghana, Botswana, and South Africa. While working there, it was hard to walk away with only reports and program ideas. I realized I wanted to do more with my hands to immediately impact the communities.

That’s why I ended up going to medical school. Orthopedic surgery is not a specialty readily available in many countries. I hope to practice a sort of mixture of public health/orthopedics.

What have you been up to since you graduated from Hopkins?

Besides work, studying, and doing research, I still love to write. At Hopkins, I took a lot of humanities courses and had friends who majored in Writing Seminars. This cultivated a love of reading and writing that I still do in my spare time.

What are some of your proudest post-graduation achievements?

Keeping up with my Hopkins friends. I love my new friends that I’ve met since graduation, but there’s something about the friends you make during college—that transitional period of your life—and the impact they make on who you are for the rest of your life that’s inimitable.

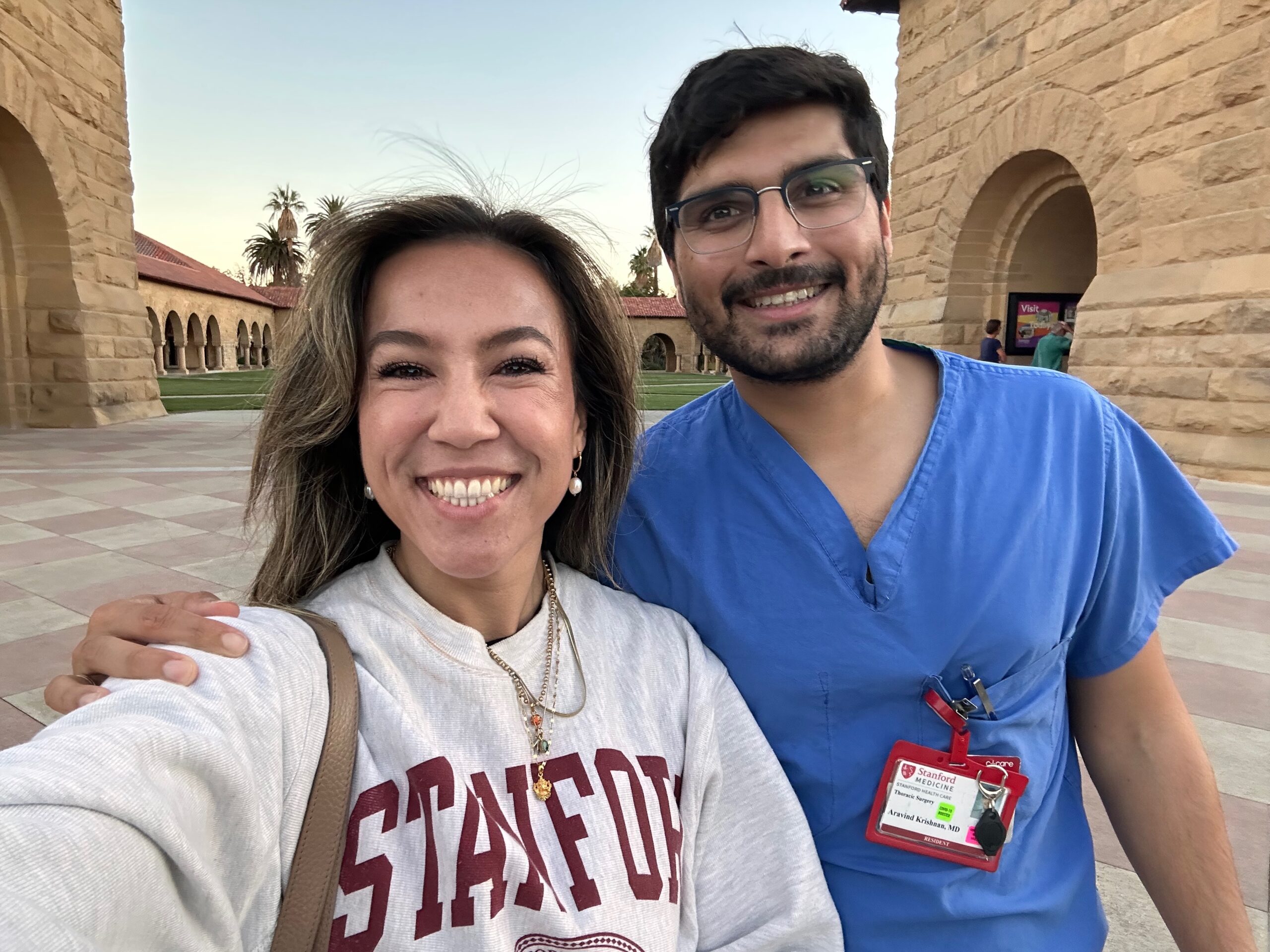

Since graduation, I’ve visited my college friends as far as Paris, London, Texas, and California. Here in Georgia, I’ve reconnected with two other Hopkins grads, and we meet monthly for dinner. My college friends also helped me network between jobs and when I was looking for residency.

Since you graduated, how have you stayed connected to Hopkins?

Besides HARC (Hopkins Alumni Representatives Council), I’m on the Alumni Council.

I think the Alumni Council is the most important thing I do to stay connected. As a student, you don’t realize what the Alumni Council is doing and how they impact education and help advise decisions that impact alumni from all campuses.

Getting to know people from different generations and branches of the school is fun. I’ve gotten to know Hopkins in a different way since graduating.

What are some of your favorite memories from Hopkins and Baltimore?

It’s hard to choose. I was on student government for all my time at Hopkins, but my final year I ran for executive president and won. I learned that I was the first Black woman to win that position, so it meant even more to me.

That’s how I got to meet some of the people in the Alumni Council. One of my mentors at the time has become like an aunt to me now.

The other is a bit of a sad moment. During my time at Hopkins, one of my friends lost their dad and it was the first friend in our group to lose a parent. We were at the dining hall getting food together and helping her coordinate flights back home. That was when I knew I would be friends with these people forever.

What about your Hopkins experience had the greatest impact on you?

The second week of classes I was in a chemistry class. The professor started lecturing and everything was going over my head. I looked around, and people were following the lecture and raising their hands and answering the questions. In that moment I realized I would never walk into a room and be the smartest person again.

My ego was hurt, but at the same time I recognized there were 200 people in this room who were so much smarter than me, and that’s how I met my best friend because she was so good at chemistry.

It was nice to know that I will never know the answers more than anyone else.

Since that wake-up call, even when I walk into a patient’s room in the hospital, I don’t ever assume I know more than anyone else. The patient is the expert in their disease, and they’re telling me what their symptoms are and how they feel. Hopkins taught me not to be threatened by not knowing the answer to things.

One of my favorite things about the neuroscience major was Dr. Linda Gorman who would always say, “We have no textbooks in neuroscience.” She would explain that neuroscience is being discovered and written about every day. There’s no textbook you can buy that’s going to tell you what you need to know moving forward.

It changed my schema of how to be a lifelong learner. I don’t need to know the right answer. There’s no one book or one person that knows all the answers and life is more open-ended.

How did your Hopkins experience help prepare you for your career?

In the neuroscience major, we had no multiple-choice question tests because you would provide an answer then justify it. There was no single right answer. “Think outside the box” was how my education was framed.

I ask “why” a lot. It’s made me a good medical researcher. When we’re fixing a fracture, for example, I’m not just like, “The plate goes here. The screws go here.” I ask, “If the screw goes here, can we skip this screw? It could save the patient money, save operative time, perhaps even improve outcomes.”

Did you have a favorite professor and/or favorite class at Hopkins?

I still keep in touch with them. Dr. Lisa DeLeonardis was one of the history of art professors who focused on ancient American art. She’s the reason I kept taking all these history of art classes and the person who I did my very first independent research study with. She would go to Peru for excavations and some of the stories she would tell us were about ancient medicine. It got me thinking because I’m from Ghana, and I realized there are similarities between intercontinental ancient medical practices. Dr. DeLeonardis helped me write a grant proposal and I got to go to Ghana and do a medical anthropology study, which was really special.

Another favorite professor, Dr. Larissa D’Souza, was my organic chemistry professor. I walked into her class and said, “Look, I want to be a doctor, but I’m not good at organic chemistry. We need to come up with a plan to get me through this.” And she was like, “Don’t worry. You got this.” I became a TA for the class—she is that good of a teacher. We’ve kept in touch since then, and she’s just a lovely person. And I still know chemistry to this day, so it worked out.

What has surprised you most about your field?

I’m in orthopedics now, and I think the thing that surprised me most is how little people consider public health as integral to what we do. It’s so discordant to how “I was raised” at Hopkins because no matter what you majored in at Hopkins, we always asked, “How can this impact the world? How can this change the community?” Even in neuroscience, we taught neuroscience topics to local preschoolers and kindergartners. It’s weird being in a stage where I practice orthopedics by fixing a broken leg and discharging the patient without thinking, for example, “This child got hit by a bus and broke her leg. What is going on in her community that the bus driver couldn’t see her?” There are so many structural reasons for injuries and there’s some public policy that could be optimized.

I chose to be at the end of the process where I patch you up and send you back. But I think in the next phase of my career I want to deal with the circumstances that bring people to the hospital.

There’s going to be plenty of accidents, but there’s also a lot of things that are preventable.

Why would you recommend that students interested in your field study at Hopkins?

I am going to change that question to “Why people interested in pre-med should not study science.” I grew and learned the most from my history of art classes, and Hopkins allowed me that flexibility.

You’re going to have to take biology and chemistry anyway if you’re pre-med. For the only time in your life, you can learn about a topic outside of medicine. I don’t get up and get excited about spending my whole day at a hospital. I get excited about the people I meet and the conversations I have. No one asks me about synapses and neurotransmitters. A lot of the conversations are about their life, so it’s interesting to know something more than just neuroscience because no one wants to talk about that.

Do you have any advice for students considering Hopkins?

My best advice is you can change your mind and change your mind again forever. As I said earlier, I’ve always been interested in healthcare but didn’t know what public health was. I came into Hopkins as an English major, then I changed to writing seminars, then neuroscience. You change but the core of it always stays the same—you’re eager to learn and you’re trying to find the best outlet for it. Being versatile helped me get to know people around campus and what moves me.

Every major has a different way of learning. By doing those classes because I was trying to figure out what I wanted to study, I was exposed to different ways of learning. I’ve graduated from medical school, and I still have to come home and study. It’s interesting to know sometimes I learn best by reading or watching videos.

My other big piece of advice is to get used to losing. I ran for student government all four years of high school, and I lost all four years. I came to college, and I ran again my first year and lost. My mom at this point was like, “What on earth are you doing?”

But I had ideas. And things bothered me that I wanted to change. My sophomore year I won, and I later became the president of the organization. Along the way I learned to be flexible and be okay with losing because the big win is so worth it.