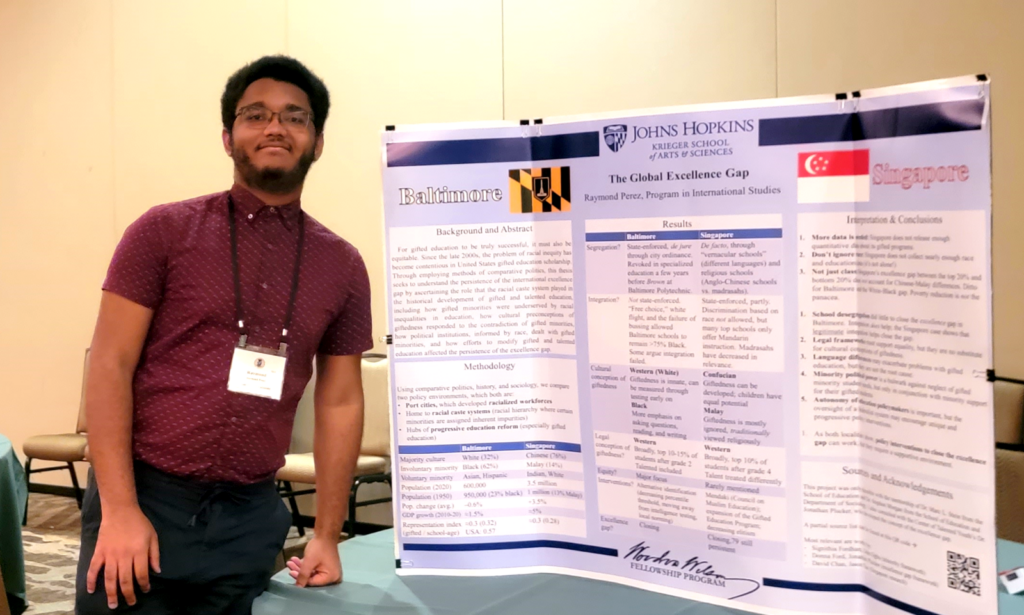

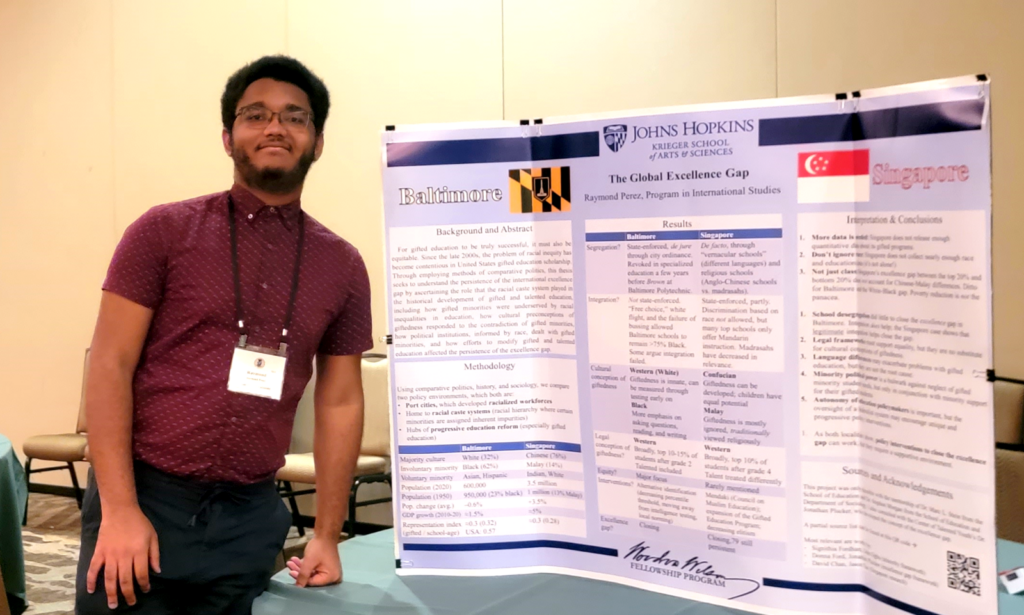

Hello, my name is Raymond Perez. It’s still surreal to be a Hopkins grad, having just finished my final project in the spring for the Woodrow Wilson Fellowship: The Global Excellence Gap. Even before I committed to Hopkins, I knew my time here would be defined by my research—after all, this is the top research university in the country. You should explore research here, even if you don’t think you’ll go into it after college.

There are so many opportunities to get support for your ideas here. The Woodrow Wilson Fellowship, for instance, is a fellowship that provides $10,000 to study basically whatever you want. You find a faculty mentor who guides you in creating your own project—but it’s entirely self-run. You will be the primary author of your paper. It’s on you to find out what that means.

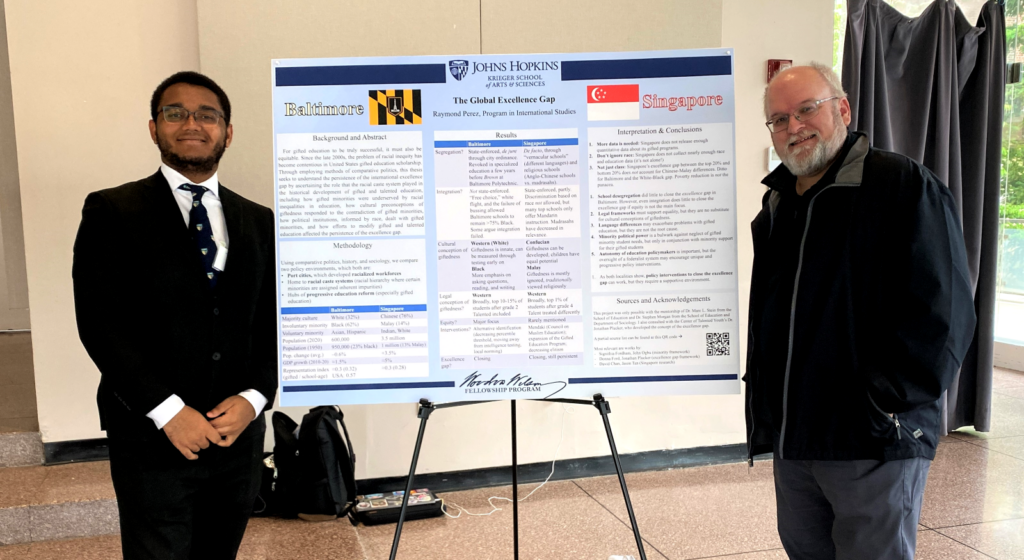

For me, that meant diving into what I found most interesting at Hopkins: Education policy, sociology, and political science. So, my project was a comparative sociopolitical analysis of gifted education in Baltimore and Singapore. This was the very first international analysis of the excellence gap—defined as the disparity in academic achievement between different subgroups of students—because analyses of the excellence gap tend to focus on national environments. To do this, I had to talk to a lot of people—from the School of Education and Center for Talented Youth to the National University of Singapore and students at Nanyang Technological University. Even though the project was run entirely by me, it required input from mentors, researchers, students, and even friends from high school.

Let’s talk about the research itself. You’re probably more familiar with the American context: White Americans tend to do better on standardized tests than Black Americans. Yet, you might not know this is especially true in the upper echelons of achievement. The top 10% of White Americans score better than the top 10% of Black Americans, and White Americans disproportionately make up the top 10% of each grade. A surprising number of researchers have argued that this disparity can be resolved simply by increasing overall achievement. But this is a questionable proposition: If you are in the top 10% of your grade, you are given more opportunities because you will be identified as gifted and thus entitled to gifted enrichment programs.

This isn’t a quirk within the American system. No, it exists in countries around the world. The majority population often has higher gifted identification than the involuntary minority population. Involuntary minorities (minorities made through colonization or slavery, such as Native Americans, Black Americans, etc.) are contrasted with voluntary minorities (immigrant minorities like Asian Americans) because they view the education system differently.

At least that’s according to a robust segment of education theorists. To put this idea to the test, I chose Singapore, a city quite like Baltimore historically with a majority Chinese population and an involuntary minority Malay population. The question you’re probably thinking right now is the top question I get when I present this: How are these two cities similar? Well, both have Anglo-inspired political institutions, and are port cities whose economies were defined by which races performed certain jobs (the racialized caste system), and both were the first in their region to develop gifted education. There’s more in the book I published, but we’ll leave it here for now.

Inspired by the literature, I looked at three points of divergence: The history of race and gifted education, what it means to be gifted, and how political institutions responded to gifted minorities. First, both societies have similar histories, but there are clear differences. Baltimore had enforced segregation; Singapore never did. Yet, both racial caste systems responded to gifted minorities by denying their existence, thus strangling their ability to advance within the social elite. They are not exposed to other successful gifted minorities, so they grow up believing—often rightfully—that their giftedness will not be recognized by the broader system. Second, Baltimore and Singapore have differing conceptions of giftedness, both with each other and within their society. The Black and Malay-Muslim conceptions of giftedness differ from the White and Chinese-Confucian conceptions of giftedness in real ways.

To grossly oversimplify, White and Confucian conceptions of giftedness tend to associate giftedness with personal morality. Minority concepts tend to focus on the community. This has downstream effects on the social and cultural incentives of being gifted, which further entrenches the problems associated with disparities in gifted identification. Finally, political institutions respond to giftedness partly as a function of minority power, but this is highly dependent on cultural conceptions of giftedness. If I had more time, I would have put a lot more focus on this part of the project, but deciding what to research is always a trade-off.

Overall, I loved my time at Hopkins—especially the research opportunities here. I would not trade my research project for any other, and my unique research was only possible through the expertise and coursework available at the university. As I look ahead toward law school, I know the discipline and hard work that my independent research project taught me will be indispensable.